Sometimes the most important stories are the ones that

end.

Death came for Anthony Reid on a Sunday—June 8th, 2025, to

be exact—and if you’ve lived long enough in this world, you know that Sunday

deaths carry a particular weight. They arrive quiet-like, slipping through the

cracks between Saturday night’s last call and Monday morning’s alarm bells,

finding you in that soft, vulnerable space where even the strongest among us

let their guard down.

The news broke the way news always does these days—through

the blue-lit purgatory of social media, where grief gets packaged into

280-character epitaphs and Instagram squares. Chatib Basri, a man who

understood numbers better than most understood people, found himself wrestling

with words that refused to add up to anything meaningful: “My friend and

teacher, historian Anthony Reid, has passed away. He not only read Southeast

Asia but listened to it.”

Listened to it. Now there’s a phrase that would make

most academics squirm in their leather-bound chairs. But Reid—Tony, as his

friends called him, the kind of man who’d correct you gently if you got too

formal—he understood something that most ivory-tower types miss entirely:

History isn’t just ink on paper. It’s the whisper of wind through rice paddies,

the creak of merchant ships riding monsoon swells, the prayers of the faithful

echoing off mosque walls at dawn.

The tributes came flowing in like water through a broken

dam. Nezar Patria, Deputy Minister of Communication and Information, posted on

Instagram—because even government officials grieve in pixels now—writing with

the kind of raw honesty that cuts through bureaucratic double-speak: “I am

deeply saddened. Farewell, Anthony Reid, often called Tony Reid. His monumental

works on the history of Aceh, Indonesia, and Southeast Asia will continue to

live and enlighten generations to come.”

But it was the young historian FX Domini BB Hera who really

got it right, who understood that the measure of a man isn’t found in his

bibliography but in the small, sacred moments that reveal his soul. Nearly two

decades had passed since that meeting at Juanda Airport in Surabaya, but Hera

remembered it like it happened yesterday—the way Tony and his beloved Helen had

barely settled into the car before asking about the nearest Catholic church,

needing to find their way to Sunday mass even in a foreign city.

“Wow, how religious,” Hera had thought then, and maybe there

was a touch of surprise in that reaction, because in our cynical age, we don’t

expect our scholars to be seekers, our intellectuals to be believers. But Tony

Reid was both, and that combination—that willingness to dig deep into the

earthly while keeping one eye on the eternal—that’s what made his work sing.

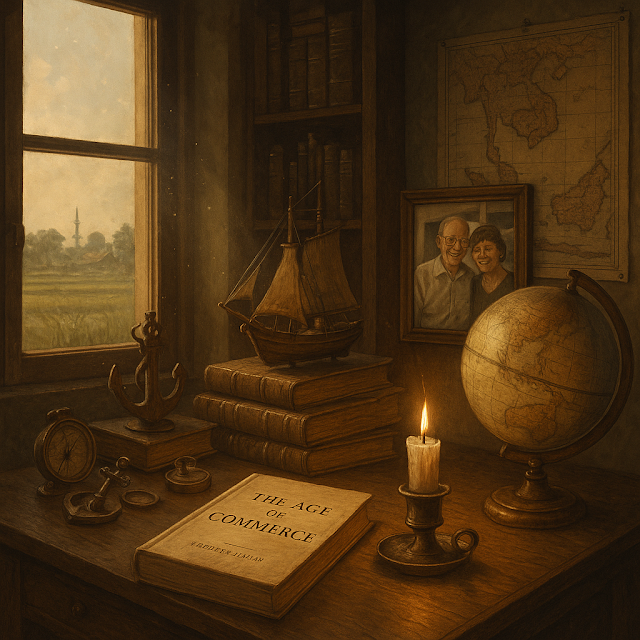

The Age of Commerce. Two volumes that changed

everything, translated into Indonesian as Asia Tenggara Dalam Kurun Niaga

1450-1680. If you’re not an academic, those titles might sound like cure

for insomnia, but trust me on this: Reid’s work was anything but boring. He had

a gift—the kind of supernatural ability that the best storytellers possess—to

make the distant past feel immediate, urgent, alive.

See, most historians, they write about the past like it’s a

museum exhibit: keep your hands to yourself, don’t touch the glass, whisper if

you must speak at all. But Tony Reid wrote about Southeast Asia like it was a

living, breathing organism, something with blood pumping through its veins and

air filling its lungs. He wrote about clothing and festivals, about food and

sex and the way men and women moved through their days six hundred years ago,

making those long-dead merchants and sultans and farmers feel as real as your

next-door neighbor.

The French have a term for this approach: histoire totale—total

history. It was Fernand Braudel who first applied it to the Mediterranean, but

Reid took that concept and made it his own, like a musician taking a familiar

melody and finding new harmonies hidden in the spaces between the notes.

Because Southeast Asia wasn’t the Mediterranean, couldn’t be contained by

European frameworks or academic orthodoxies. It was something else entirely: a

constellation of islands and cultures connected not by land but by water, by

trade winds and monsoon currents and the ancient human drive to explore what

lies beyond the horizon.

Born in New Zealand on June 19, 1939—midsummer in the

southern hemisphere, when the light stretches long and the air holds that

particular quality that makes you believe anything is possible. Young Tony Reid

must have felt that possibility in his bones, because when he was just

thirteen, he followed his diplomat father to Jakarta and fell in love with a

nation that was still finding its feet, still learning how to be free.

That love affair lasted a lifetime. Cambridge University,

where he met Helen (Gray) and married her in 1963. Teaching posts at the

University of Malaya, Australian National University, UCLA, the National

University of Singapore. Two adopted children, Kate and Daniel, because

sometimes family is less about blood and more about choice, about the people

you decide to love and keep loving even when the world goes sideways.

But it was that first encounter with Sumatra that really

hooked him. His doctoral dissertation became The Blood of the People in

1974, and the title tells you everything you need to know about Reid’s approach

to history. Not the clean, sanitized version they teach in survey courses, but

the messy, complicated, human truth of it all. Blood and struggle and the way

ordinary people get caught up in forces beyond their control, the way

revolutions have a habit of eating their own children.

The establishment noticed. In 2002, while directing the Asia

Research Institute at the National University of Singapore, Reid received the

Fukuoka Asian Cultural Prize. Standing there in his acceptance speech, he said

something that reveals the man behind the scholar: “I feel very fortunate and

deeply honored. I am extremely grateful to the Indonesian government for

opening its doors wide to the world. This is one of the most important events

in my career.”

Gratitude. In an age of academic ego and intellectual

territorialism, here was a man who understood that knowledge is a gift, not a

possession. That understanding other cultures isn’t a right but a privilege,

one that should be approached with humility and respect.

The French historian Lucien Febvre once told a story about a

dying king who asked his vizier to summarize all of human history in the

moments before death. The vizier’s answer was brutal in its simplicity: “Your

Majesty, humans are born, love, and die.”

But Reid understood that such reductionism, however poetic,

misses the point entirely. Yes, we’re born and love and die, but in between

those markers, we eat and drink and dress and work and pray and fight and

dream. We build cities and tear them down, create art and destroy it, tell

stories and forget them. We’re messy, contradictory, beautiful, terrible

creatures, and any history that ignores that complexity isn’t history at all—it’s

fairy tale.

Tony Reid refused to write fairy tales. He wrote about

corruption and scandals, about the way holy men sometimes sold scriptures for

personal gain, about the blood-soaked politics of spice trade ports. He wrote

about Southeast Asia not as some exotic paradise but as a human space, complete

with all the light and shadow that entails.

This wasn’t the sanitized orientalism of earlier scholars,

men who came to the region carrying the white man’s burden like a suitcase full

of good intentions. Reid’s orientalism—if we can call it that—was honest,

unflinching, grounded in respect rather than condescension. He understood that

the people of Southeast Asia had their own stories to tell, their own ways of

making sense of the world, and his job wasn’t to impose European frameworks but

to listen, to learn, to translate.

“It was the scholarly activities of the orientalists that

began the heroic task of recovering and making accessible the written legacies

of the Southeast Asian peoples themselves,” he wrote, and in that sentence you

can hear the humility that made his work so powerful. He wasn’t trying to be a

prophet or a savior. He was just a pilgrim, wandering through cultures not his

own, gathering stories and sharing them with the world.

The thing about storytellers—the good ones, anyway—is that

they never really die. Their bodies fail, sure, the way all bodies do, but

their words keep drifting on the wind, settling into new minds, sparking new

questions, opening new doors. Tony Reid’s words are out there right now,

somewhere, being read by a graduate student in Manila or a curious teenager in

Banda Aceh or a policy maker in Washington who’s trying to understand why

Southeast Asia matters.

As Pramoedya Ananta Toer once wrote, “Writing is working for

eternity,” and Tony Reid put in his time. Six decades of it, from that first

glimpse of Jakarta in 1952 to his final breath on June 8th, 2025. He leaves

behind a body of work that will outlive us all, a map of Southeast Asia drawn

not with colonial arrogance but with scholarly love.

The last page has turned for Anthony Reid, but the story he

spent his life telling? That story’s just getting started. It’s drifting with

the wind and waves, journeying to every corner of the world, waiting for the

next reader to discover its treasures.

And somewhere in the vast library of human knowledge, Tony

Reid’s voice whispers on, reminding us that the best histories aren’t just

about what happened, but about why it matters, and how it connects to

everything else, and what it means to be human in a world that’s always

changing but somehow, mysteriously, always the same.

Sometimes the most important stories are the ones that

never end.

Comments

Post a Comment